Building on students’ experiences with moving image makes preparation for GCSE English Language, Paper 1 Question 3 engaging and enjoyable

The introduction of structure as a focus of assessment in GCSE in AQA’s GCSE English Language Paper 1, Question 3 was a welcome shift toward thinking about the bigger picture of how stories are ‘built’ to be compelling.

Since the first iteration of the specification, Question 3 has been reworded to focus the question on a single effect to help students formulate their answers and support them in writing succinct, relevant responses. Students are also provided with extra guidance in the bullet points by giving generic structural features that they could comment on.

Narrative structure can be an exciting aspect of Key Stage 3. We can find creative and exciting ways of teaching students about structure as a way of building compelling stories, we can explore the relationship between fiction and moving image and consider the effects of shifts in narrative perspective.

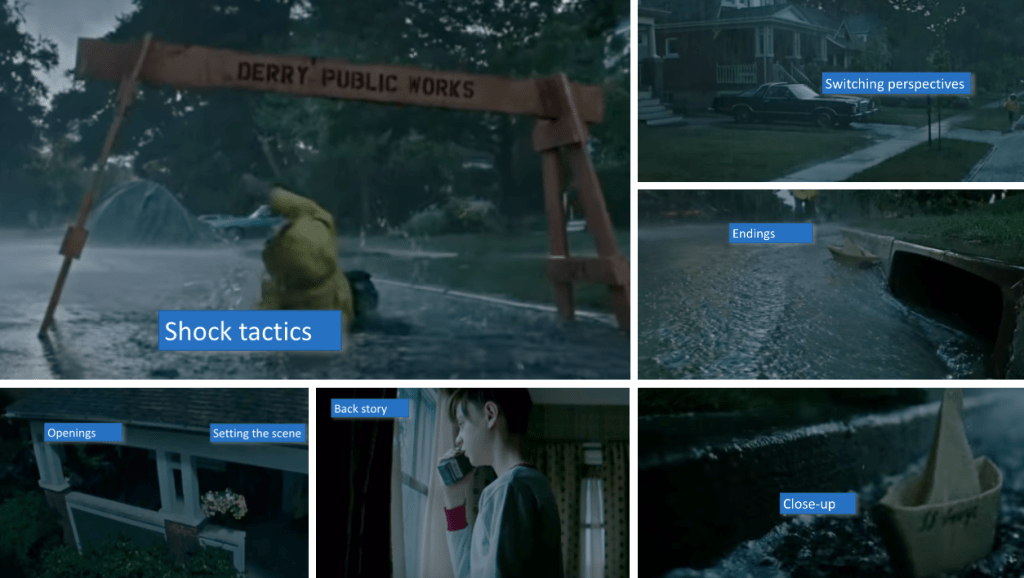

At Key Stage Four, when preparing students to respond to AQA’s GCSE English Language, Paper 1 Question 3, it can be productive to build on students’ prior knowledge of narrative structure, especially by exploring the links between prose and film. Structure can be conceived as something that happens in terms of whole stories — scene setting, inciting incident, exposition, climax — but also within sequences, scenes and chapters.

Although the previous wording of Question 3 asked the student to think about how the text has been structured to interest the reader, the new wording helpfully focuses on a specific intended impact. To this, end, it’s helpful to discuss the purposes of structure in various forms. A castle, for example, has a defensive structure, whereas a spring has a flexible structure for movement. A skeleton is structured for both flexibility and support. These analogies can be useful when we’re considering the purposes of narrative structure — which is, essentially, to make fiction compelling.

Screen short films in the classroom, as structurally speaking, they’re compact but complete

‘Many [students] can now recognise where the structural shifts in a source occur and are able to track the sequence, but greater consideration of why the writer has made a particular choice at a particular moment and how that impacts the reader’s understanding of the whole is needed.’

Report on the examination, June 2018

Big Buck Bunny — a 2008 short computer-animated comedy film by the Blender Institute — works really well as a way of exploring structure. In the animated film, the eponymous protagonist decides enough is enough when faced with a pack of small mammalian bullies. The simple narrative sequence of ‘beginning, middle and end’ is a useful starting point for discussion with students, then screen grabs can be distributed which they can annotate with helpful key terms — and most importantly — intended impact. How is character established? How does the focus change as the short film progresses? What is the impact of specific structural techniques, such as the zoom-in when Big Buck Bunny decides to tackle the bullies head-on?

‘An increasing number of students were confident in their approach to what is still a relatively new skill. They did not over-complicate the question and there was far less over-reliance on subject terminology or high level literary/narrative theory.’

Report on the examination, June 2018

Try a hands-on approach and get students editing

‘The most successful students understood that the story was a construct. They offered an overview of the structure of the whole source before breaking it down into its constituent parts and analysing the shifts in perspective and focus in a way that clearly explored their significance.’

Report on the examination, June 2018

Getting students to work with moving image can create an immersive and exciting lesson. The dramatic opening of Enduring Love (2004, dir. Roger Michell) is an ideal starting point: although it is clearly the first part of a larger narrative, it immediately draws the viewer in through its intensity and tension. This makes it a strong text for encouraging discussion about how a story can grip an audience from the outset, while also offering a clear illustration of narrative structure.

One way of approaching this is to take a short excerpt from the film and import it into Windows Movie Maker or a similar editing program. The software automatically divides the sequence into smaller sections which, while not exact cinematic shots, provide manageable clips for students to experiment with. Each of these clips can be saved individually to a shared network drive, allowing students to access them and edit them into their own sequences. Once they have produced a version, they can compare it with a partner’s and discuss how the editorial choices they have made affect the viewing experience and shape the story.

The same principle can also be applied in PowerPoint, where students can arrange stills or short clips in sequence and annotate them with key terms. This offers a more accessible but equally valuable way of thinking about structure and meaning.

Through whole-class discussion, students are encouraged to reflect on the choices they have made and to articulate the impact of placing one shot before another. By being specific about how these choices influence the way a viewer interprets events, they begin to develop a more analytical awareness of moving image and the ways in which editing contributes to storytelling.

Pair moving image clips with their prose partner

When students gain confidence in considering how a film-maker has structured a piece of moving image to make it compelling, they often transfer that confidence to handling written texts. The analytical processes they develop through film can be built upon in reading, making connections between the two media both natural and engaging. A particularly useful approach is to pair extracts, beginning with the moving image clip and then moving on to the print passage, encouraging students to explore similarities and differences in the way each text grips its audience.

Having worked with students on the Enduring Love editing sequence, it is fascinating to see their response to the ways in which McEwan deploys comparable structural devices in prose. The novel’s opening, for instance, lingers on Joe’s close-up, almost cinematic, description of opening a bottle of wine before the shocking appearance of the hot air balloon. The deliberate shift from the mundane to the extraordinary creates an incongruity that echoes the effect of the film’s opening sequence, demonstrating how narrative structure can destabilise and arrest the reader just as it does the viewer.

Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men provides another valuable example, particularly in its cinematic qualities. McCarthy frequently structures his writing into sequences that resemble film scenes, and the extract in which Chigurh escapes custody is especially effective for teaching about transitions. The abrupt movement from interior to exterior is handled with a blackly comic edge, showing how shifts in space and perspective can be as striking in prose as in film.

The opening of Stephen King’s It offers a different but equally rich model. Here, King clearly sets the foundations for an epic story, but he also uses specific structural features to immediately draw readers in. The stormy weather introduced at the outset becomes a recurring motif, while the back story of Bill Denbrough and his vulnerable younger brother George layers characterisation with a sense of foreboding. By juxtaposing an intimate family moment with the ominous backdrop of a storm, King establishes both atmosphere and narrative tension in a way that resonates with the cinematic strategies students will already have encountered.

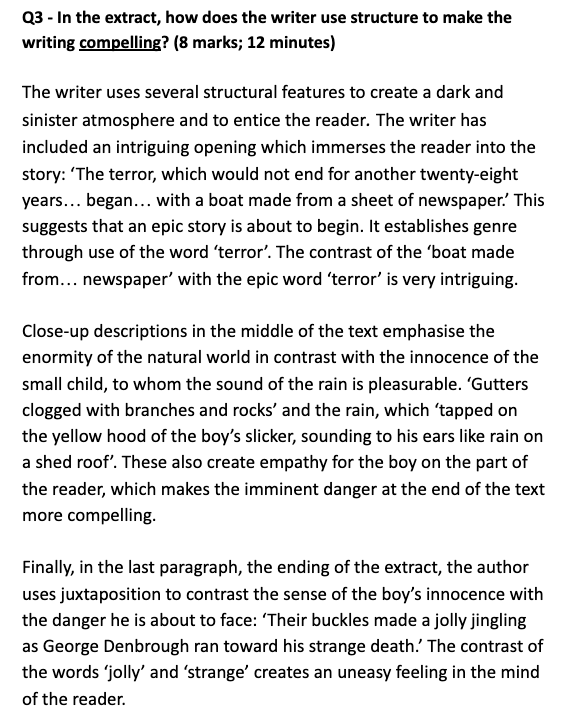

Model the process of writing a response

‘They looked for patterns and were able to make links and connections between different parts of the source, and they explored contrasts and juxtaposition of both ideas and tone.’

Report on the examination, June 2018

Live modelling is a great way to show students the process of making a written response. Although it’s tempting to write a response earlier and share it as a ‘here’s one I made earlier…’, demonstrating the process itself is very valuable. It’s helpful to highlight which parts of the model answer are really analytical. Using verbs such as ‘entice’, ‘suggests’, ‘intruiges’ and ’emphasises’ are useful in that they showcase students’ awareness of the text as a construct.

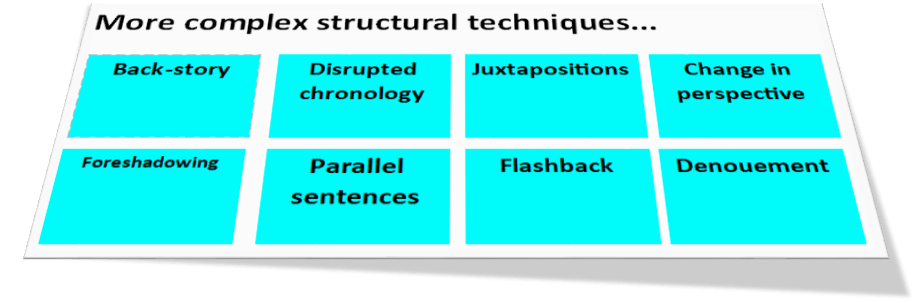

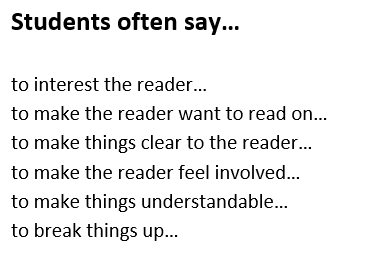

Encourage students to be more precise when exploring effects

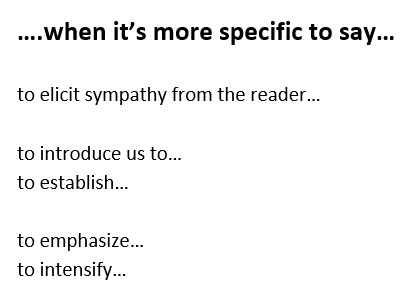

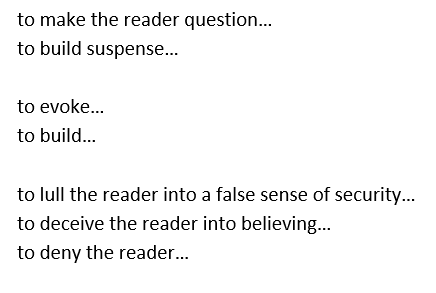

When exploring the effects of language and the layers of meaning in words and phrases, analytical signposts such as ‘this suggests’ or ‘this implies’ are commonplace. But being aware of the intended impact of structural features can help students to be more explicit about how these features affect the reader. A shift in perspective might, for example, reveal part of the narrative. A transition from outside to inside might intensify the mood. It’s worthwhile sharing some of these more specific phrases with students and encouraging them to experiment with using them in their responses.

And finally… examiners’ words of caution

‘There are still a significant number of students who write that an aspect ‘interests the

Report on the examination, autumn 2020.

reader’ or ‘makes the reader want to read on’. These responses cannot be credited

above Level 1.’

‘One unhelpful trait was writing about the construction of sentences, as in Question 2,

Report on the examination, June 2018

rather than the position of key sentences and the significance of their placement.’

Featured image: Photo by Mathew Schwartz on Unsplash