An intuitive sequence of learning can simplify your planning, provide your department with a common language to talk about teaching and learning and help ensure progression for your students.

Software engineers at Apple – so the story goes – had spent months working on elaborate interfaces for an app that allowed users to burn video to DVD. But when CEO Steve Jobs was shown the designs, he jumped up and drew a simple rectangle on a whiteboard.

‘Here’s the new application. It’s got one window. You drag your video into the window. Then you click the button that says “Burn.” That’s it. That’s what we’re going to make.’ Jobs understood that simplicity doesn’t have to be superficial: we can make things better not by putting stuff in but by taking stuff out.

So it can be with planning. I argued in a previous blog post that in a subject as multi-dimensional as English, it’s crucial that with our focus on planning curriculum sequences that teach substantive knowledge (factual content such as word classes, narrative theory or the historical the context of texts we read) we don’t limit strong disciplinary practice (the processes by which we read for meaning, listen to interpretations and write to respond) in the classroom.

Of course our long-term curriculum should be robust, well-sequenced and should bring together the study of different domains, forms, genres and ways of writing. But if the ensuing medium-term planning is an overly prescriptive model that specifies exactly what will be learned and when, it can limit opportunities to let teachers find new ways, to experiment, to take different pathways and it can impede their own professional development. It can also result in planning that doesn’t quite fit how readers and writers in the real world think and work.

I wanted to explore how a sequence of reading and writing that reflects what we do in the real world might look. I captured a sequence of phases which is designed to serve as a guide for when we’re planning a scheme of learning, but also which reflects the sequences and processes we as teachers might facilitate in smaller units of learning, during each week and in each lesson. Each stage builds upon the previous one, enabling a progression in students’ understanding and engagement. Students progress from initial exposure to ideas to deeper engagement with texts and their responses to them, ultimately developing their skills in critical thinking, analysis, and communication.

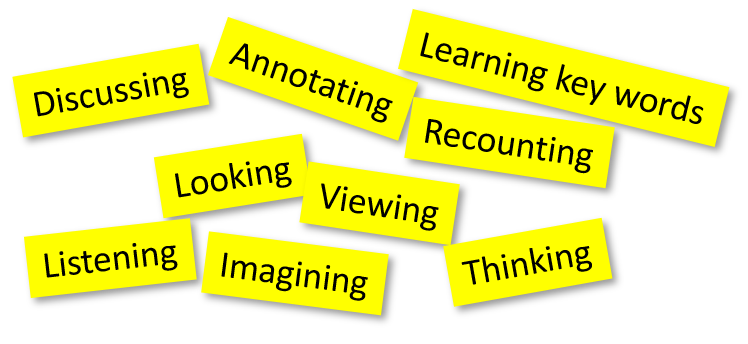

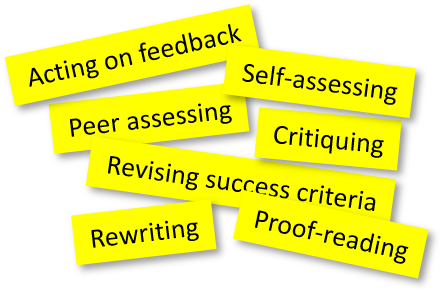

As the image at the top shows, I’ve indicated what typically could be happening in the classroom at each phase of the sequence. I conceived this in terms of things the students might be doing, but it goes without saying that these learning activities will be facilitated by the teacher, offering varying degrees of independence and with the teacher instructing, explaining, modelling and scaffolding throughout. At the same time, the teacher will employ various types of questions at each stage.

I tested a ‘beta’ version of my thoughts by sharing a version of the image at the top on social media. This garnered some positive affirmation as well as some helpful feedback. One person said they wished they could just submit the image as their medium-term planning for schemes of learning, as it captured the sequential essence of what happened in their classroom. This was an encouraging comment, as it felt like the essence of the sequence had resonated as a helpful conception of good planning.

I’m planning to follow this blog post up with a series of subsequent ones, each of which will explore a phase of the sequence in more depth, explaining how the student activities associated with it might best be practised and considering how teacher-talk and questioning can be used to facilitate learning. But before that, I wanted to introduce the sequence and outline the importance of each phase. I hope it’s something that might be helpful.

1. Encountering themes, forms, and ideas

The first stage of the sequence introduces students to the overarching themes, forms and ideas they will encounter. It sets the foundation for deeper exploration and understanding.

As English teachers, we can employ a variety of activities to introduce students to encounters with themes, forms, and ideas before reading a text. James Durran has written about the importance of the pre-reading activity: ‘…entering the intellectual and imaginative territory of the text and of the lesson – priming pupils to think figuratively and to think about the connections between apparently disparate ideas.’

One approach can involve discussing the author, the historical or cultural context of the text, or related themes, fostering critical thinking and contextual understanding. However, viewing images or a series of curated images can visually engage students and spark their curiosity about the themes and ideas they will explore. Students might offer describing words, for example, to bring together their thoughts and obervations about Gothic images. They might explore a painting and work out what’s depicted and what tone it creates. For instance, I often ask students to consider ‘The Iron Rolling Mill’ by Adolph Menzel before teaching Romanticism.

Incorporating moving images can further enhance students’ understanding by illustrating concepts and making connections between the text and real-world examples. A non-fiction article, poem or short story can pique interest and stimulate thinking and great classroom discusion, especially if it’s unusual, provocative or unexpected.

2. Reading texts

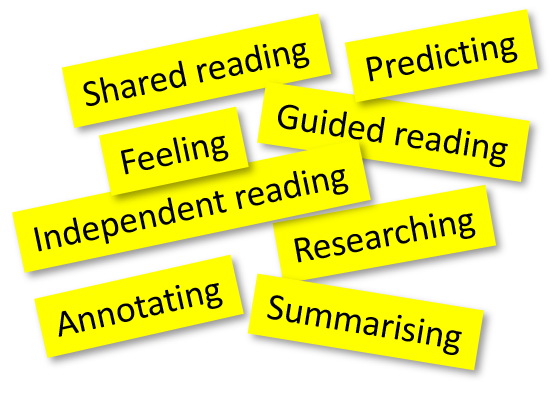

The second phase of the sequence is one of the most important pillars of the English classroom – reading. This usually involves reading a variety of texts—such as non-fiction, novels, poems, plays, or films—that exemplify the themes and forms they’ve encountered earlier in the first phase. Again, we have a toolkit to help students make the most of reading. It could be how we organise the reading (shared as a whole class, guided reading in groups or asking students to read individually) or it could be how we model and teach the elements of reading, such as decoding and reading for meaning.

Shared reading (often the most widely used form of reading in the secondary classroom) involves the teacher and the whole class reading a text together. As teachers, we typically select a text that is slightly above the students’ independent reading level but accessible with support. This helps build students’ fluency, comprehension, and language skills. It also provides opportunities for students to engage in discussion, ask questions, and make connections to the text as a group. During the reading, we might pause at strategic points to ask questions, make predictions, clarify vocabulary, facilitate discussion and to model the process of what happens when we read, including what happens when we experience ambiguity, misunderstanding or discomfort. Shared reading can also involve activities such as interactive read-alouds, where students actively participate in the reading of the text.

During guided reading, the teacher works with a small group of students who are at a similar reading level. During this activity, we provide targeted questions and support as students read texts that are at their level. This approach allows us to focus on specific skills and strategies tailored to the needs of individual students or small groups. It provides opportunities for feedback, and reinforcement of reading skills. We can model strategies such as decoding unfamiliar words, using context clues, and making predictions. Guided reading sessions often include discussion questions, comprehension activities, and opportunities for students to demonstrate their understanding of the text.

Independent reading involves students reading self-selected texts on their own. Students choose books based on their interests and reading level. This approach can foster a love of reading, improves reading fluency, and promotes self-directed learning. It allows students to practice applying the skills and strategies they have learned independently. However, we can talk with individual students to discuss their reading progress, offer recommendations, and provide support as needed.

3. Responding informally to texts and ideas

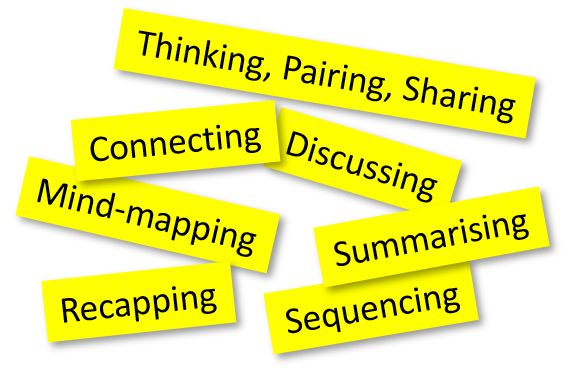

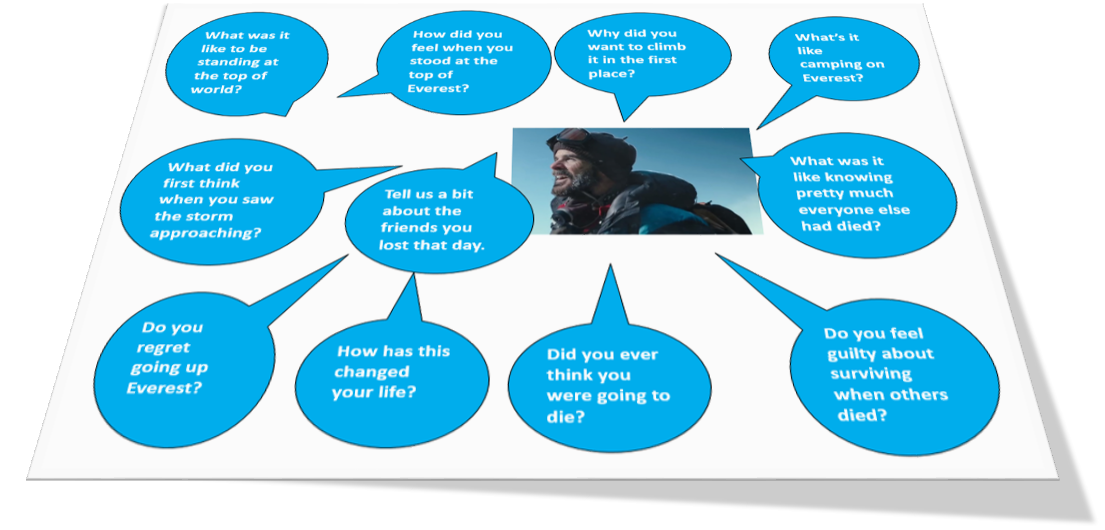

During the third stage, students engage in informal responses, discussions and other reflective activities as a means to articulate their initial reactions, thoughts, and interpretations. This could include visual tools such as the ‘tell-me grid’, ‘idea capture’ or ‘reading bubbles’.

‘What did you think about this character?’ we might ask when leading discussion. ‘What surprised you?’ ‘What genre do you think the story could fit into?’

We might ask students to make connections to previous learning and encounters with texts: ‘Does this remind you of anything?’ ‘How does this link to what we read back in Year Seven?’

We might provide visuals or quick-fire activities for students to do. This approach not only encourages active engagement with the content, but also promotes critical thinking and the development of individual perspectives. By allowing students the opportunity to express their initial responses in a variety of formats, we can show the value of diverse modes of expression and encourage students to explore their understanding through meaningful dialogue and introspection.

4. Planning writing in response to texts and ideas

In the fourth part of the sequence, students can be given the opportunity to make a response to what they have read and experienced, as writers do in the real world, so the sequence of learning works toward the planning of a responsive writing assignment which is drafted and re-drafted.

I’ve suggested before that reading and writing should be very closely aligned, so students see themselves as apprentices, bringing language and literature together and removing boundaries around the domains of reading and writing. This writing could take many forms. It could, for instance, be re-creative, exploratory, analytical or imaginative. Responding to a text doesn’t always have to take the form of structured analysis.

Showing students how to plan responsive writing involves engaging in thorough mind-mapping sessions, creating detailed outlines, and carefully considering how they will articulate their responses to the texts and ideas they’ve encountered. The process of modelling sequencing, or how to structure a response, is of paramount importance. For example, I’ve created various movable structures to project, asking students to consider the impact on the reader when we move the elements into different configurations.

Of equal importance is teaching students to consider the form, audience and purpose of the text they’re going to write. It’s helpful to frame this as something which, as the sequence progresses, could be open to change and improvement, rather than as a list of fixed ‘success-criteria’ (the one term from the image at the top that most people didn’t really like during my social media test).

Consequentially, students can develop more nuanced and insightful perspectives, effectively integrating these insights of codes and conventions into their writing, perhaps initially in an exploratory way. This process not only enhances their critical thinking abilities but also empowers them to communicate their ideas with clarity and precision.

5. Drafting the writing

This fifth phase enables students to refine their writing skills and express their ideas. Building on their planning and retrieving ideas and information, students start drafting their written responses. This stage is a crucial step in the process as it allows students to transform their initial concepts and ideas into a cohesive written piece.

As they engage in this process, students are not only refining their ability to convey their thoughts effectively but are also strengthening their capacity for critical thinking. Returning to texts previously encountered, using style models, scaffolding and live modelling, the teacher can demonstrate the process of writing text and the importance of paying attention to the planning structures previously worked on. It’s a great opportunity for the teacher to model how grammar works in practice, demonstrate how codes and conventions can be applied and sometimes subverted for effect.

6. Editing and re-drafting

During the sixth phase of the sequence, the students refine and enhance their initial drafts through a process of editing and re-drafting. They engage in a review of their work, evaluating the clarity, coherence, grammar, and style of their writing. The teacher can deal with misconceptions, offer feedback, make suggestions and model how students can overcome barriers. Students might productively spend time peer assessing each other’s work. It could also be productive to critique and revise success criteria established during the fourth part of the sequence.

This in-depth review enables students to make necessary revisions aimed at strengthening their writing and ensuring that their ideas are effectively communicated to the reader. By carefully examining each aspect of their composition, students can elevate the quality of their work and produce a more polished final version.

Final thoughts

By following this sequence of stages, students progress from initial exposure to deeper engagement, ultimately developing their skills in critical thinking, analysis, and communication within the context of the English classroom. By aiding students to recognise the connections between reading and writing, as well as comprehending the common structures, themes, and literary devices found in texts, we empower them to discover their unique voice and use it with conviction.

For teachers, I hope the sequence offers a natural progression of learning for the English classroom that can streamline planning and offer department colleagues some shared reference points of good practice. The activities for students – as well as the aspects of teacher-talk and use of questioning I’m planning to explore in the subsequent posts – could offer clear focuses for CPD.

In the follow-up blog posts, I’m going to explore each stage of the sequence in more depth, highlighting good practice, considering how the activities students are doing can be used most effectively and how we as teachers can support students through talk in the classroom and through questioning. I’ll be reaching out, via social media, to canvas opinion and to ask for ideas, so feel free to get in touch if you’d like to contribute!

Featured image by Nick Fewings on Unsplash