This question offers some really great opportunities for students to productively engage with the idea of thinking and writing analytically

Teaching AQA’s GCSE English Language Paper 1 is a brilliant way to explore the craft of fiction. As well as the specimen material and past papers available online, it’s always fun to choose texts for teaching that really engage students, both in terms of content and style. Question 4 particularly offers some really great opportunities for students to engage with the idea of thinking and writing analytically in response to those texts.

Since the first iteration of the specification, AQA has removed the reference to a ‘student’ making a statement in Question 4. This helps our students focus on the statement itself, encouraging them to make a critical judgement about the writer and the text, rather than responding to an imaginary student voice.

The second bullet has also changed from ‘evaluate’ to ‘comment on’ methods. This clarifies that the emphasis is on evaluating the text in relation to the statement, supported by analysis of the different methods the writer has used.

The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris

‘This question has the highest tariff: at 20 marks, it is half the marks available in Section A and 25% of the marks available for the whole paper. It should therefore be the most challenging of all the reading questions.’

Report on the Examination, June 2017.

I ask students how they’d imagine a serial killer who ate his victims to be. How would this person look? How would they act? How would they speak?

Students often focus on the stereotypical image of a ‘cannibal’ as deranged and impulsive, although some, already familiar with The Silence of the Lambs (1991, dir. Jonathan Demme) might point out that Sir Anthony Hopkins’ iconic portrayal of Thomas Harris’s antihero has shaped our cultural conception of what a ‘cannibal’ might be like.

I explain to the uninitiated that the character of Dr Hannibal Lecter is a psychiatrist turned serial killer who ate his victims and consequently is incarcerated in a maximum security facility. In order to obtain Lecter’s professional insight into a new serial killer case, the FBI have sent rookie agent Clarice Starling to interview him. I screen the clip from the movie, being careful to stop at 1 min 30 seconds, before the expletive after Lecter asks Starling: ‘Multiple Miggs in the next cell. He hissed at you. What did he say?’ I ask the students for their first impressions on the character of Lecter. Is he what they expected? If so, how come? If not, why not?

At this point I ask the group for their immediate responses to Lecter. Is he what they imagined after hearing that he is a cannibalistic serial killer? Very often, students expect a monstrous, grotesque figure, someone visibly violent or deranged. Instead, they encounter a man who is calm, articulate, and courteous. His civility is striking: the way he greets Clarice, the precision of his speech, and the quiet control he exerts in his cell all contribute to an impression that runs counter to the brutality of his crimes. It is precisely this contrast — between the audience’s expectations of a cannibal and the cultivated elegance of Lecter — that makes him so disturbing.

However, an alternative reading often emerges in class discussion. For some viewers, Lecter’s very composure is what makes him frightening. His unwavering eye contact, the sense that he is appraising Starling rather than simply speaking with her, and the way he commands the space from behind bars suggest manipulation and control. Far from being reassuring, his politeness can feel like a performance designed to unsettle, a reminder that beneath the surface there is a predatory intelligence at work.

By exploring both perspectives, students can begin to see how the film offers no single ‘correct’ response to Lecter. Instead, it plays on ambiguity, using characterisation to keep the audience both fascinated and uneasy. This tension provides a rich opportunity to analyse how filmmakers use performance, dialogue, and visual choices to shape audience reactions in complex and often contradictory ways.

We then read the extract from Harris’s novel. It’s interesting to talk with the students about how the presentation of Lecter in the film is similar and different to the Lecter of the novel. The absence of the ‘net’ in Jonathan Demme’s version of Lecter’s cell often intrigues the students, as does the absence of the extra digit on Lecter’s left hand.

Exploring the demands of the question

‘Students were asked to what extent they agreed with the statement… and they… [are] at liberty to completely agree, completely disagree, or agree with some aspects and disagree with others. All evaluations and interpretations are valid, as long as they are rooted in the source.’

Report on the Examination, June 2018.

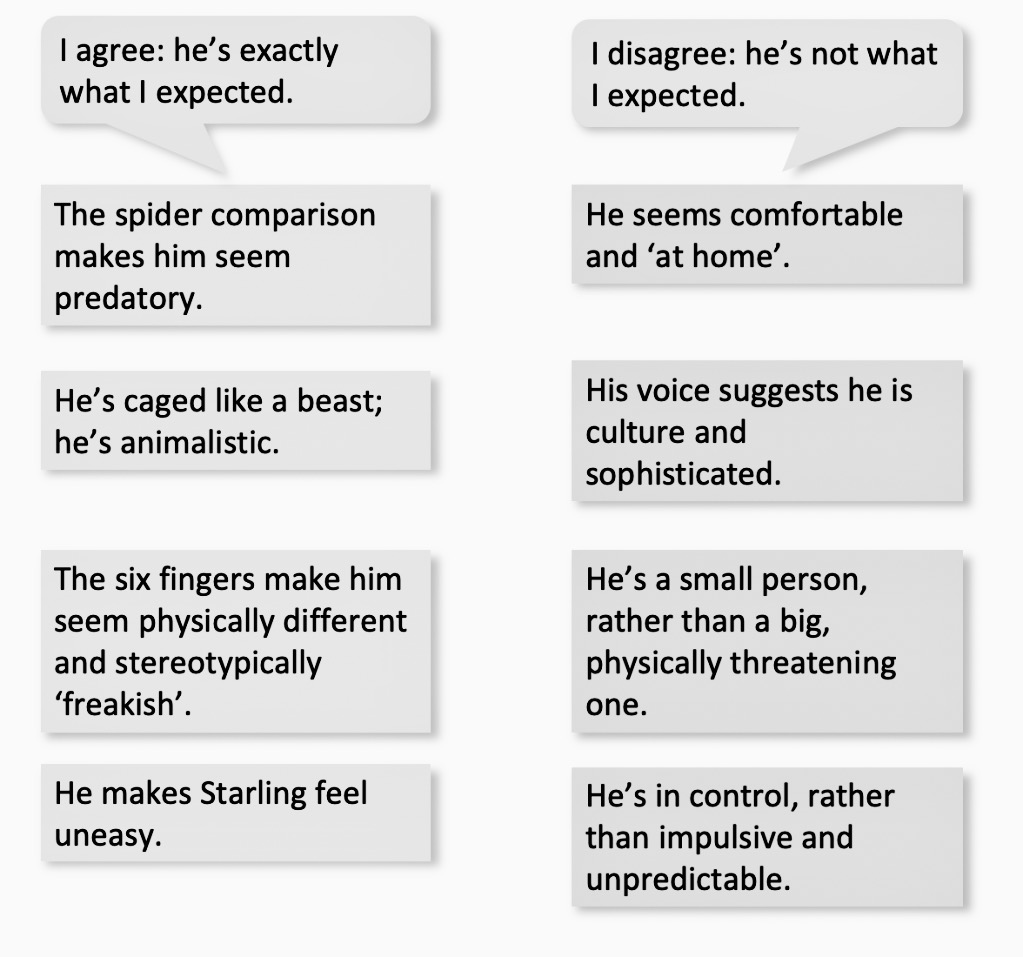

I then introduce the class to the exam question and its demands. We consider how the question encourages the candidate to respond to the statement in one of three ways: agree, disagree or partially agree. I ask which of these three possible responses the statement – ‘Dr Lecter wasn’t what what I expected a cannibalistic serial killer to be like!’ – generates.

Modelling reading the text and choosing ideas to support a response

I then ask students to explore possible ideas from the text that supports their argument, for example. ‘He seems rather polite for a serial killer,’ one student might comment, or ‘actually, there’s something sinister about his controlled behaviour,’ another might suggest.

Some of these can often work for both. For example, some students feel that Lecter’s sense of self-control supports their assertion that he’s a stereotypical cannibalistic serial killer as he’s self-assured and sinister. Others, however, feel that this is at odd with their expectations.

Modelling the process of making a response

I model the process of responding by starting with a direct, balanced judgement on the statement, then showing — briefly and live — how to build that view from evidence and method. With the Lecter extract, I explain that the task is to respond to the statement, and to justify how far we agree by commenting on how the writer’s choices shape meaning and impact. I might begin: ‘I largely agree that Lecter is unsettling precisely because he is civil; his politeness and composure subvert expectations of a cannibal, though moments of control tip that civility into menace.’ I then write a short paragraph in real time, exploring methods such as diction and the power dynamic with Starling, so that students can see how comments on method link directly to impact.

I encourage them to keep their own responses focused on impact too, moving beyond simply naming techniques: not ‘Harris uses formal vocabulary,’ but ‘Harris’s formal vocabulary distances Lecter from brutality, making violence feel more chilling because it coexists with refinement.’

Though demanding, this question is enjoyable to teach because it strengthens wider analytical skills. Students learn to decide what they think, explain why, and examine methods critically — all habits that can be transferred to other texts across the course.

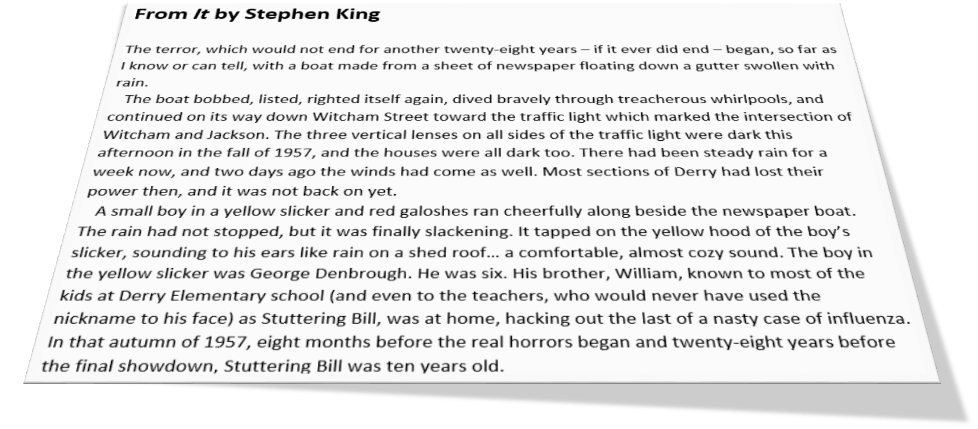

It by Stephen King

Another text that works powerfully with Question 4 is the opening of Stephen King’s It. At first glance, it seems disarmingly innocent: a boy in a yellow slicker chasing a paper boat through the rain. The detail is vivid and comforting — the ‘cozy’ sound of rain on George’s hood, the ‘jolly jingling’ of his galoshes — images that wouldn’t feel out of place in a children’s story. And yet, King carefully undercuts this mood with ominous hints: the failed traffic lights, the wreckage of storm-damaged streets, and the narrator’s chilling foreshadowing that George is running ‘toward his strange death.’

This tension between innocence and dread is exactly the kind of ambiguity that gives students a way into Question 4. A statement such as ‘The opening creates a sense of safety rather than danger’ immediately prompts discussion: do we agree, disagree, or partially agree? Some will argue that George’s cheerfulness and the comforting tone of the narration do create a sense of safety. Others will point out the darker undercurrents: the foreshadowing of death, the violent imagery of floods, and the fact that readers already sense something is lurking beneath the surface.

Modelling critical engagement

I model how to build a response by showing students that both interpretations can be justified, depending on the evidence they select. One student might argue that King’s description of George’s happiness, the ‘solitary, childish glee,’ reassures the reader, inviting us to see this as a moment of innocence before danger intrudes. Another might counter this by pointing to King’s ominous narration — ‘the terror… began with a boat’ — which signals from the outset that danger is ever-present, undercutting any sense of safety.

In both cases, the key is to connect method to impact: King’s use of foreshadowing, his juxtaposition of cozy detail with sinister suggestion.

Transferable skills

Working with this extract demonstrates to students how effective writers manipulate tone and perspective to play on readers’ expectations. Just as with The Silence of the Lambs, they can see how apparently contradictory readings (safety vs. danger, innocence vs. threat) can both be supported by the text. This not only prepares them for Question 4 but also cultivates the habit of holding two ideas in tension — a hallmark of sophisticated analysis.