I was intrigued to see how the provision of a ‘fictional construct’ might bring about effective learning connected to story-telling

Early in my teaching career, I taught a sequence of learning to Year Eight, delivered principally from a text book, which was based around the premise of students as applicants for an interstellar space mission. As part of the sequence, students were exposed to a range of non-fiction texts, such as applications, CVs, persuasive letters and non-chronological reports, and would learn the codes and conventions of these texts and how to use them.

I suggested to the department members that there was a huge amount of scope for the premise to become much more multi-modal. The focus could be expanded beyond non-fiction text types to consider the science fiction genre and its associated codes and conventions at large, to which students could respond creatively.

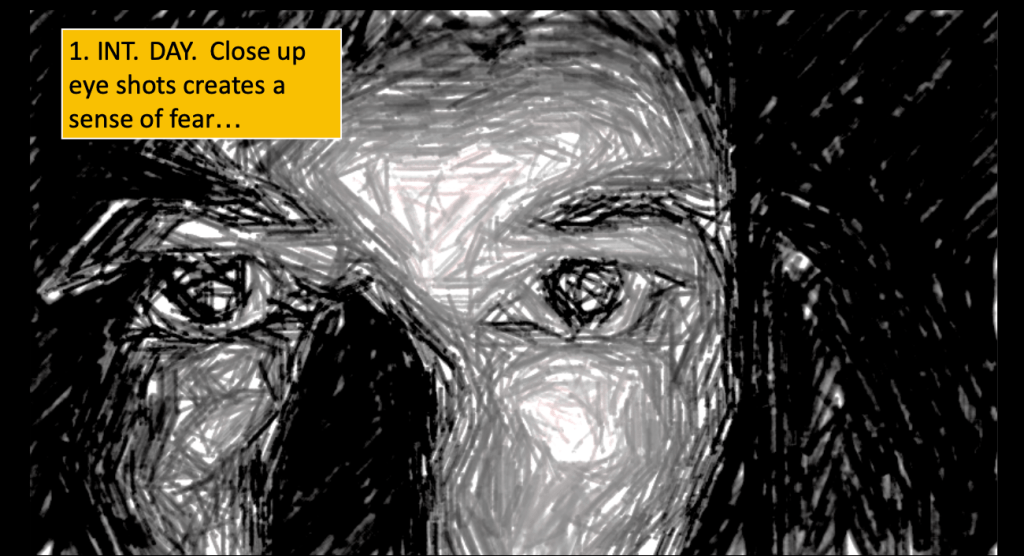

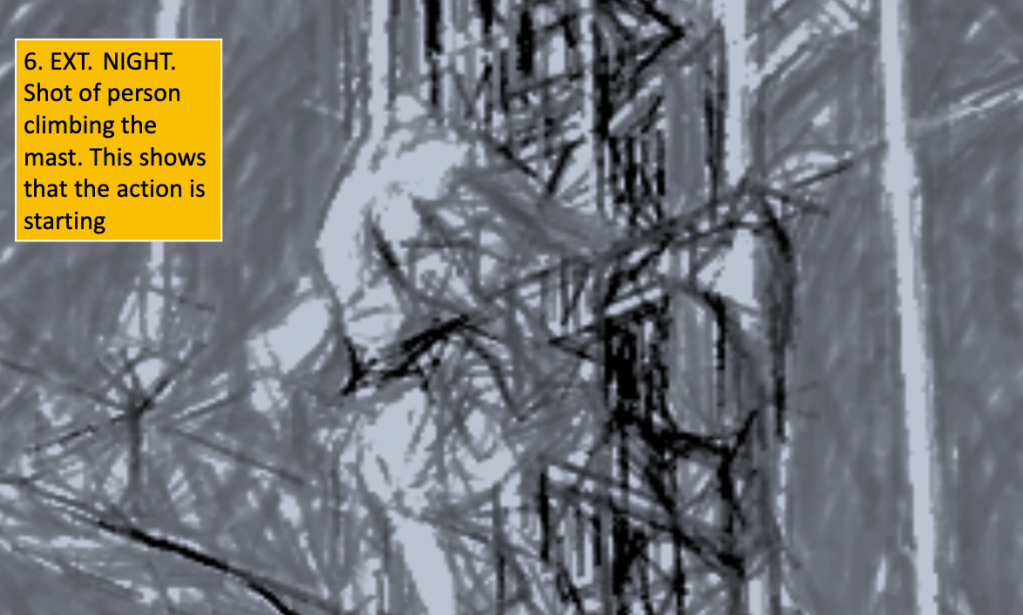

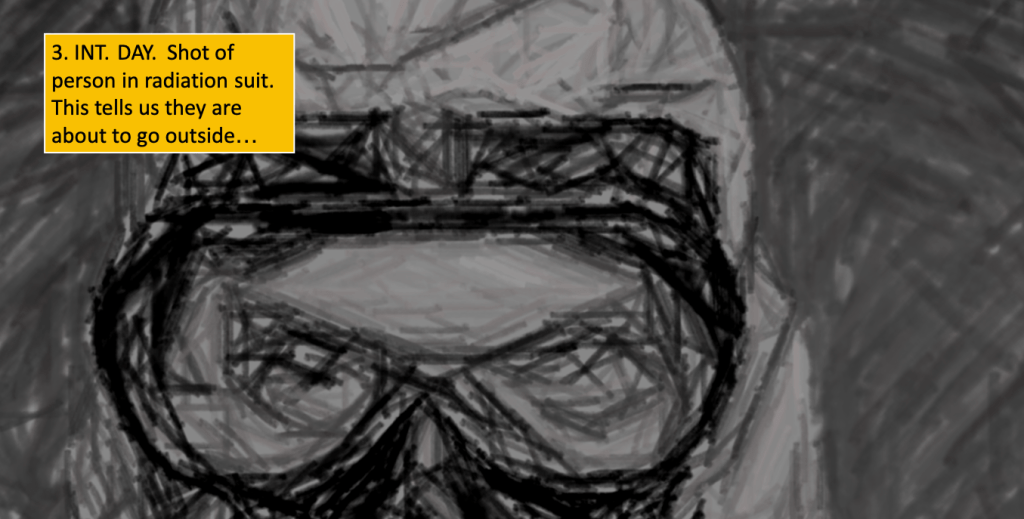

At around the same time, I had began my first year of teaching A-level media studies. I set the students from this class an exercise which involved story-boarding, scripting and shooting sequences based around the same scenario the Year Eight students were working on, with the intention of using these moving image prompts as part of the scheme of learning. I had stumbled up on the idea not only of moving image as a creative writing prompt, but also on the idea of what I called the ‘fictional construct’, an immersive narrative arc which is ‘seeded’ by the teacher, but developed and made whole by the students. Hence, the space exploration sequence became a way of teaching a variety of text types, but with creativity firmly at the centre, to which the Year Eight students responded enthusiastically.

Fictional construct as collaborative creativity

I was lucky enough to continue teaching this group when they moved into Year Nine, and when it came to the summer term (this was a time when teacher autonomy was liberally encouraged) I asked whether they’d prefer to spend those weeks reading and studying an existing text (I was thinking about a drama version of The Chrysalids by John Wyndham as a stimulus for creative writing) or whether they’d prefer to collaborate on a brand new story. They unanimously chose the latter.

As a teacher of drama as well as English and media studies, I was intrigued to see how the provision of a ‘fictional construct’ might bring about learning connected to story-telling, to unpack the concepts and structures we all know are implicit in stories but the schema of which we rarely pause to deconstruct. I also wanted to use aspects of all three of these disciplines to encourage students to see the common threads of story-telling and to understand the impact of multimodal thinking.

My first instinct was to establish a scenario that created a mystery of some kind. This was around the time I had spent many hours watching Lost (2004-2010; Jeffrey Lieber, J. J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof) on television, and I was inspired by the questions it posed, not just in terms of the enigmas at the heart of its own storylines but also about the nature and structure of stories themselves and how the viewer or reader can easily find their perception of narrative outcome, protagonist and antagonist obfuscated for dramatic effect.

I rather liked the idea of a sinister leader. Benjamin Linus from Lost was obvious inspiration. I played around with various contexts, such as a remote, desert-based cult, in which each student would be given a role they would assume throughout the entire scheme of learning. I even took this idea as far as pricing up gospel-choir style robes.

But then a different scenario emerged. What if the students were inhabitants of a strange community; ostensibly survivors of some kind of apocalypse, living together in a series of underground bunkers? In creating this ‘fictional construct’, I laid the ground in advance. I displayed teaser posters around school with embedded QR codes which the students could scan and learn clues about the origins of the narrative (this was before there was any inkling of banning mobile phones in schools). Prior to the teaching sequence beginning, this attempt at ‘viral marketing’ had established the notion of The Sanctuary, the community of survivors to which each of the students, in role, would belong.

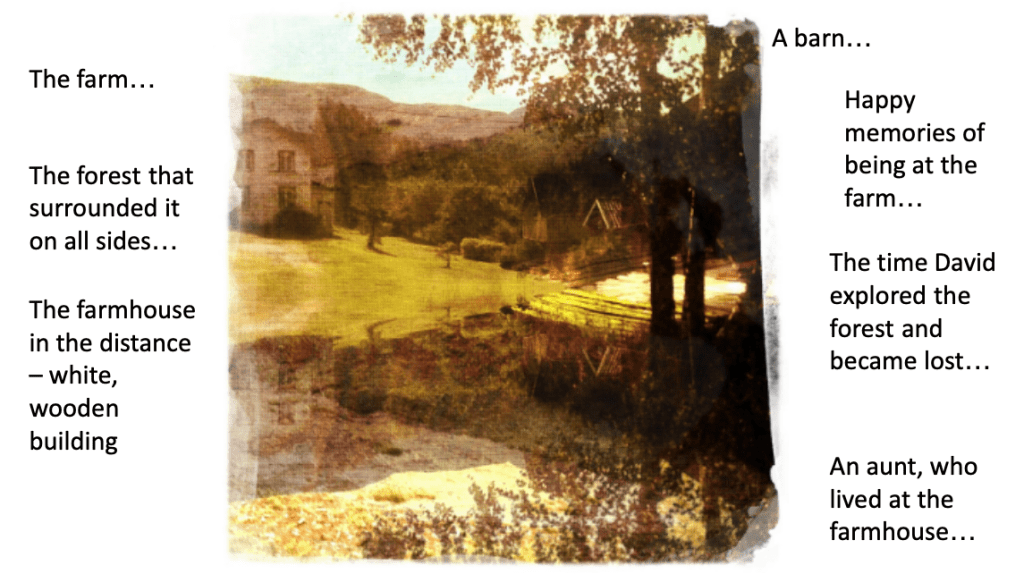

I assigned each student a name and gave them a ‘Polaroid picture’ from the lives they had only vague memories of. The students explored their new characters, attempting to ‘recover’ memories of their barely remembered, pre-trauma past lives in a kind of ‘going clear’ process. Of course, I was asking them to think hard about creating a protagonist and narrator that they would use as the basis of their creative writing. As the pictures below indicate, the students used the ‘Polaroid pictures’ to think about their character’s backstory.

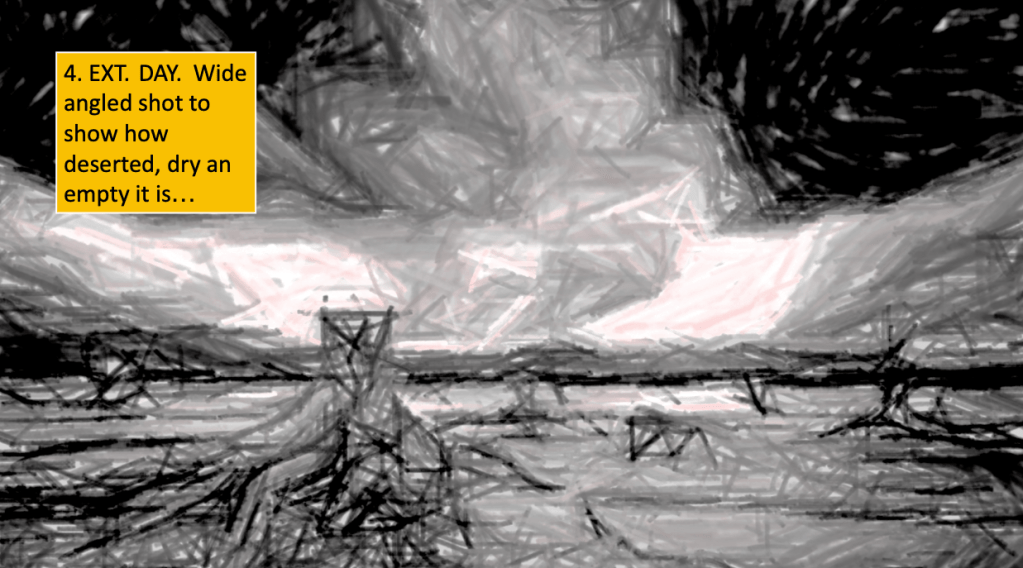

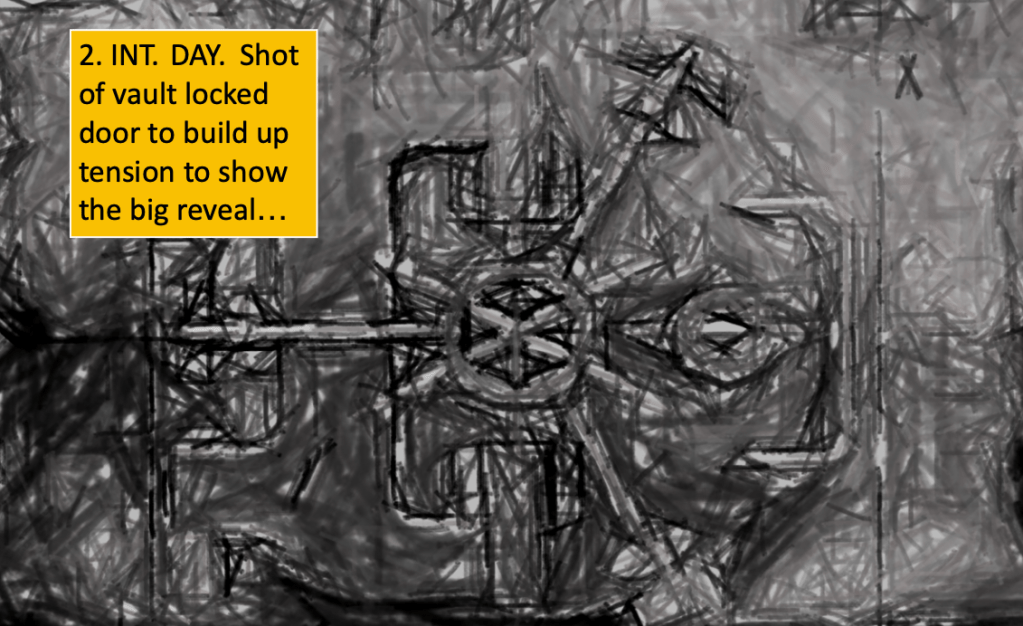

We then explored the idea of establishing narrative equilibrium, thinking about the community we lived in, describing the daily routines, relationships and tasks. I modelled each piece of creative writing from the perspective of my role as David, the sinister leader-type figure. Writing was focused around narrative voice and building tension through, for example, events such as the characters being forced to leave the confines of the community to repair a malfunctioning radio mast.

I modelled the process of planning and writing a monologue from the perspective of my character, David

The sudden departure of my character, David, from the narrative allowed the students to write a climactic piece that details their escape from the community and the their characters’ realisation that the world they believed they were part of is a conceit: they are essentially the subjects of a psychological experiment conducted by an overarching pseudo-scientific research organisation (I should point out this was a couple of years before James Dashner published The Maze Runner).

When I first taught the scheme of learning, I was careful to shape the narrative conceit so when the week of the sequence was taught, the revelation that the students’ ‘personas’ had been duped would engender genuine surprise and outrage. This was successful. But for the second time of teaching, a year later, I was both surprised and pleased to note that rumours about the narrative trompe-l’œil had already spread amongst the class members. Therefore, to what extent, I wondered, should the students become responsible for shaping the narrative into its final form?

Faced with this is the question, I found myself giving the students more freedom to experiment with possible climaxes and resolutions, which felt like a much more exploratory way of learning.

I used found images rendered as sketches and included annotations in the form of directors’ notes to encourage students to think about how to sequence their own writing

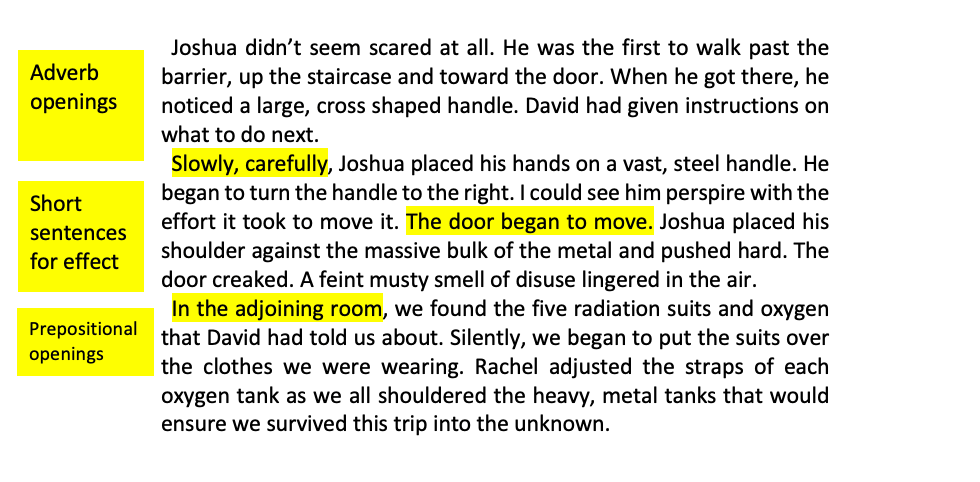

As I modelled the different aspects of the creative writing I wanted the students to work on, I drew attention to grammar in context, asking them to think about the impact of these choices on the reader.

How can ‘creative talk’ be helpful in developing writing?

Throughout the course of the scheme of learning, I attempted to experiment with other ways of using talk to enable the students to engage with the elements of creativity I was seeking. How, I wondered, could I use drama as a way of probing and prompting character and monologue? Exploring scenarios through the teacher-in-role method really helped to palpably build the ‘fictional construct’, and using the drama studio to ‘introduce’ a conflict or scenario, in role as David, then to ask the student to work in pairs or threes in developing a response, then finally, hot-seating students in character, worked well both itself but also as a means of generating creative responses that could subsequently be used in writing too.

Some of the drama we workshopped was even recorded as audio, and editing was completed with music and sound effects, as part of an exercise in multimodal texts, but also to use as models and stimulus in subsequent years, as the following audio clip attests to:

As a unit essentially focused around skills – ‘reading’ a genre and ‘writing’ in response to it, how could I ensure there was sufficient ‘knowledge’ or ‘content’ – terminology and concepts – as part of the sequence of learning? I wanted the students to become familiar with those ideas, devices and concepts connected to story-telling: the idea of the narrative arc; of climax; of protagonist and antagonist, of plot twist, of anagnorisis. I encouraged them to use these terms when talking about their own work.

Final thoughts

The use of a fictional construct in teaching dystopian creative writing demonstrates how immersive, collaborative frameworks can both engage students’ imaginations and deepen their understanding of narrative form. By blurring the boundaries between drama, storytelling, and creative writing, students are invited to inhabit characters, grapple with mystery, and co-author outcomes in ways that mirror the complexities of real-world narratives. Crucially, the teacher’s role as both model and co-creator ensures that creativity is scaffolded with knowledge of literary concepts such as narrative arc, climax, and anagnorisis. In this way, the fictional construct becomes more than a teaching strategy: it is a catalyst for collaboration, critical thinking, and authentic creative expression.